At 4:30 a.m. in Chennai, residents line up silently with buckets as a private water tanker reverses into a narrow street. By sunrise, the tanker is empty.

The price of this water has doubled since last summer. For a household earning close to the urban minimum wage, the cost of a single tanker delivery can now consume an entire day’s income, turning a basic necessity into a recurring financial shock rather than a temporary emergency.

This arrangement is no longer exceptional.

It has become normal — and that normalization is the clearest warning sign of a failing urban water system.

Across India’s cities, water scarcity has shifted from a seasonal disruption to a structural breakdown driven by design, governance, and incentive failures.

How India’s Urban Water System Is Breaking Down

Indian cities depend on a fragile combination of surface reservoirs and groundwater extraction. As urban populations have expanded rapidly, demand has far outpaced investment in sustainable supply infrastructure.

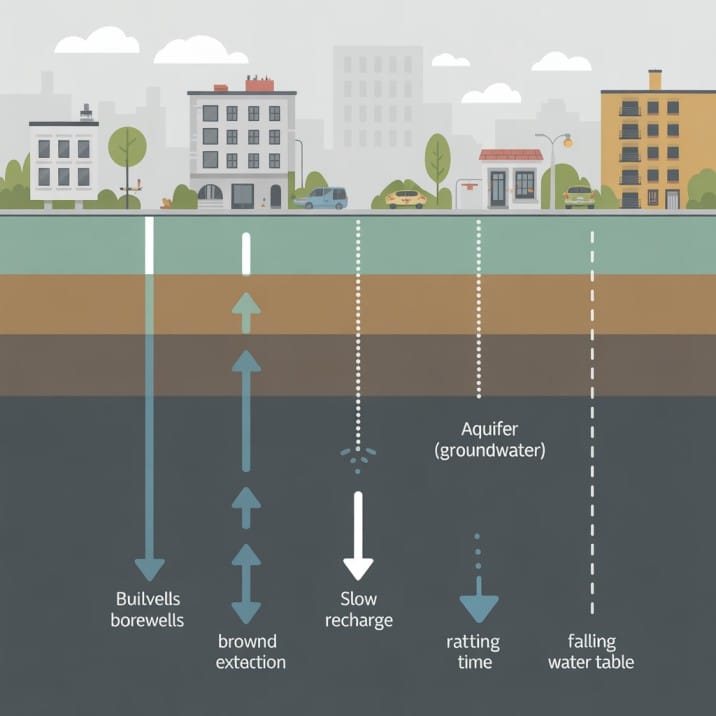

Pipelines leak, reservoirs struggle to recharge, and borewells multiply as private solutions to public failure. Over time, cities become locked into a system that extracts water faster than nature can replenish it.

This imbalance was present even before climate stress intensified. According to the World Bank, India supports nearly 18% of the global population with only about 4% of the world’s freshwater resources, placing urban systems under permanent structural pressure.

Source: World Bank – Water Resources in India

https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/india/brief/world-water-day-2022-how-india-is-addressing-its-water-needs

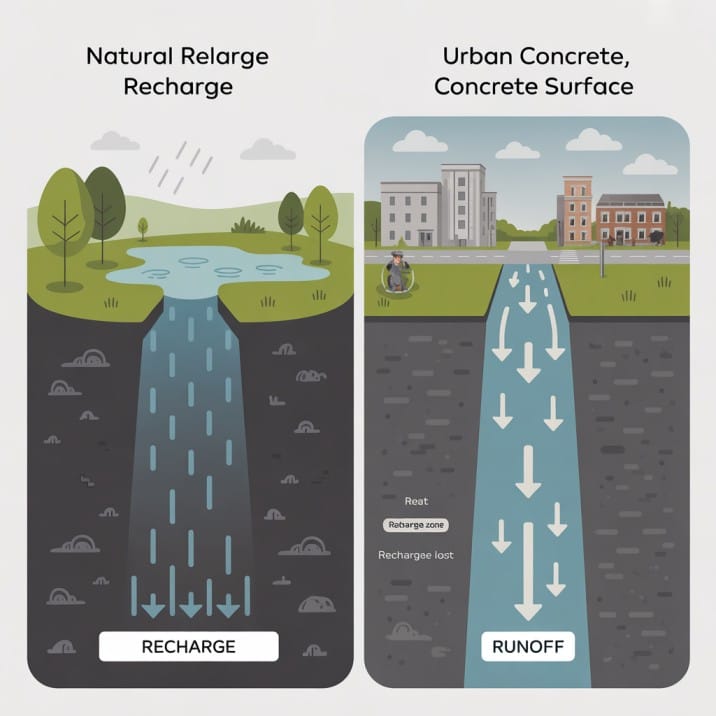

Urban expansion has compounded the problem. Concrete-heavy development has covered natural recharge zones, preventing rainwater from seeping back into aquifers. What appears to be a supply crisis is, at its core, a planning failure.

Why the Crisis Keeps Repeating Every Year

One factor dominates all others: unchecked groundwater extraction.

India is the largest extractor of groundwater in the world, according to assessments by the Central Ground Water Board (CGWB) under the Government of India. Urban overuse has driven water tables downward across major cities.

Source: Central Ground Water Board, Government of India

https://cgwb.gov.in/

In Bengaluru, one of India’s fastest-growing cities, borewells have replaced failing municipal supply at scale. As aquifers fail to recharge, households and apartment complexes are forced to drill deeper each year, accelerating depletion and raising costs.

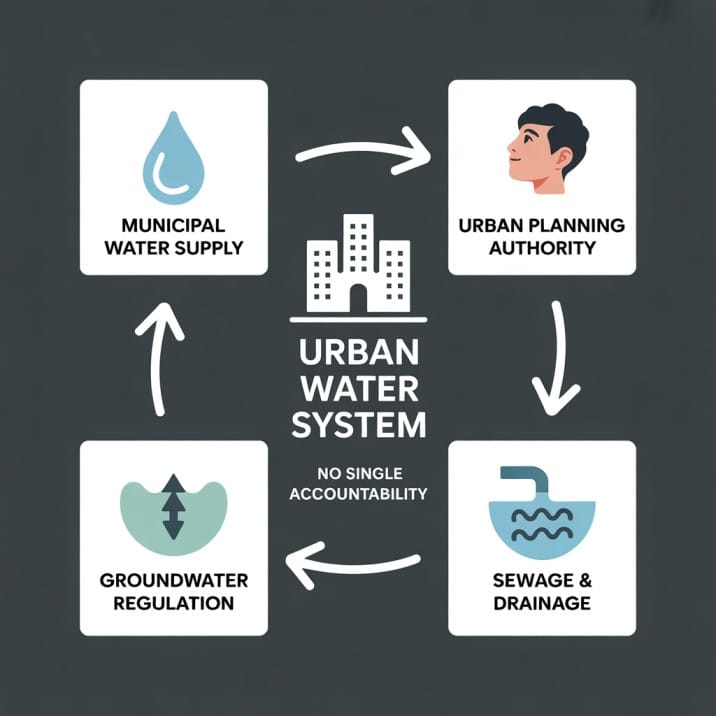

Governance fragmentation makes the problem persistent. Water supply, sewage, groundwater regulation, and urban planning are managed by separate agencies, often operating without coordination. Responsibility is distributed, accountability diluted.

Instead of structural reform, cities rely on emergency responses: deeper borewells, tanker deployment, and periodic water cuts. Each temporary fix delays long-term solutions while worsening the underlying crisis.

Who Pays the Price — and Who Benefits

For ordinary households, water scarcity means higher expenses, lost work hours, and health risks from unsafe sources. Families in informal settlements face the greatest burden, as they are often the last to receive municipal supply and the first to lose it during shortages.

At the same time, a vast private tanker economy has expanded to fill the gap left by failing public systems. While private water supply itself is not illegal, the scale of dependence reveals institutional collapse.

Public infrastructure exists.

Access increasingly depends on the ability to pay.

What the Data Shows About Urban Water Stress

Government and international assessments confirm that India’s urban water crisis is no longer hypothetical.

Several Indian cities fall under “high to extremely high water stress” categories — regions where demand approaches or exceeds available supply — as defined by UN-Water.

Source: UN-Water – Water Scarcity

https://www.unwater.org/water-facts/water-scarcity/

Climate variability has intensified the pressure. Erratic monsoons, rising temperatures, and longer dry spells are pushing already fragile systems closer to failure.

These indicators do not describe a future risk.

They describe present conditions.

How Other Countries Manage Similar Water Risks

Water scarcity is not unique to India. Cities across the world face comparable rainfall variability and population pressure.

The difference lies in governance and regulation.

In several global cities, groundwater is treated as a strategic public asset. Extraction is tightly monitored, reuse of treated wastewater is standard practice, and leakage reduction is enforced through measurable targets.

In contrast, Indian cities allow groundwater to function as an unregulated fallback. As public systems weaken, private extraction expands — not as an exception, but as a parallel system.

The result is a model where scarcity is managed, not prevented.

Why This Crisis Extends Beyond Water

Urban water shortages affect far more than daily convenience. They undermine public health, education, productivity, and social stability. When access to a basic service becomes unpredictable, inequality deepens and trust in public institutions erodes.

India’s cities are economic engines. Their long-term viability depends on systems that work reliably, not on emergency responses that normalize failure.

The Structural Conflict India Must Confront

India’s urban water crisis is structural not by accident, but by prolonged inaction. Delayed reform has allowed a scarcity-driven private tanker economy to normalize the breakdown of a public service.

Addressing this reality requires more than infrastructure spending. It demands confronting an incentive structure that profits from failure.

Until that conflict is resolved, tanker queues will remain a permanent feature of urban life — and water scarcity will continue to shape Indian cities far beyond dry taps.

5 thoughts on “Why Indian Cities Are Running Out of Water Explained for India and the World”